As I discussed in my last post on matrix management, Gemini appears to operate in more of a functional vs. a matrix management approach. The perceived principal drawbacks of the current approach is that overall project accountability is diffused and internal project handovers can be confusing and inefficient. In my previous post, I argued for a relatively small change in practice to move to a more matrix management structure. Here, I will explore other small changes in an attempt to establish a more

functional functional structure.

While the status of General Motor’s financial success is no longer so glamorous, I will use the early days of GM as a possible model for Gemini. GM was built by acquiring multiple companies that all had roles to play in the manufacture and sales of automobiles. GM consisted of companies that produced tires, batteries, electronics, car bodies, etc., as well as the companies that sold their end product to consumers (Chevrolet, Oakland/Pontiac, Buick, Cadillac, etc.). Having all the dependencies needed to make a car in house under its own control was thought to be of significant strategic value to competing in the marketplace.

Initially, however, the expected efficiency results were not realized. Alfred P. Sloan, manager of GM at the time, realized that the organization’s structure was actually stifling innovation and efficiency. If, for example, Delco learned to make a better, cheaper radio to go in next year’s Pontiac, it was Pontiac who ended up selling more cars at higher profit, not Delco. In other words, Pontiac ended up with the credit for Delco’s innovation and Delco quickly lost the desire to innovate since it received none of the credit for its improvements.

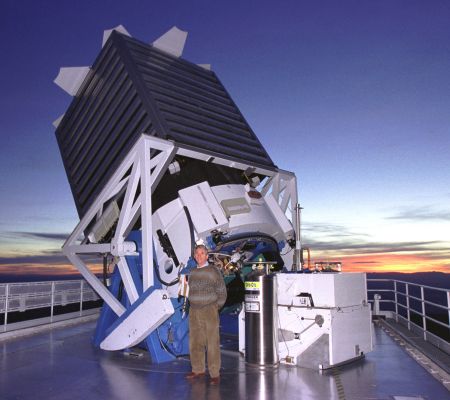

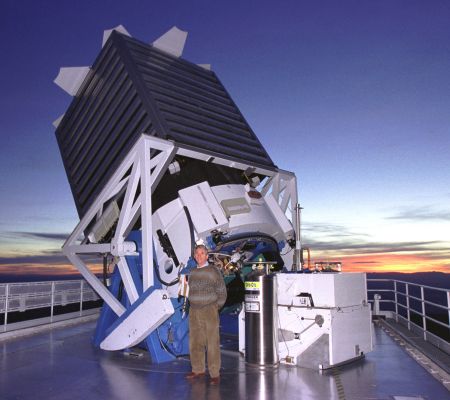

John Peoples, then SDSS Director, and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Telescope

Sloan therefore changed things so GM’s car manufacturers actually had to buy its needed components from GM’s internal suppliers. Now if Delco made a better cheaper product, Delco’s finances would improve as well as Pontiac’s. Each division’s contributions to the end product were now more clearly identified and the incentive to innovate and improve returned. GM enjoyed incredible success with this model until it was changed decades later by perhaps less-effective management than Alfred Sloan.

So how does Sloan’s approach correct the problems I stated earlier with the functional management approach? The accountability problem is addressed by increasing the visibility of each Division’s contributions to the project. The project manager or other interested overseer can readily see how each group contributed to the overall project. The project manager maintains accountability and control by having to negotiate for her needs with each external division head, essentially issuing internal contracts to provide needed project services. As a result, the miscommunications and handover issues that happen when project responsibility passes from one division to the next disappear because these interfaces are forced to be better-defined in the more formal relationship between divisions. Information transfer might still be lacking, but if the divisions are separate enough, that may not be a problem.

Is Sloan’s GM an appropriate model for Gemini? While perhaps a viable model, it is probably not the most appropriate. Too much time, and too much cross-disciplinary expertise would be needed to properly specify the requirements for external division work. Currently, we make use of the skills that exists in other divisions to help establish the needs and requirements of our projects. To adequately scope a statement of work for the electronics component of a project would likely require more engineering expertise than Development has, for example.

A twist, then, could be to have each Division responsible for determining their own set of requirements, covering the aspects of the project for which their skills are needed only. An internal virtual contract would then be let and each Division would control their own work. In the end, though, this twist ends up being very similar to the semi-functional approach we have now. Overall project accountability remains diffuse.

So what about the successful Gemini integration of Flamingos-2? While the verdict is still out on the overall success of this instrument (it is still undergoing on-telescope acceptance testing), its integration into the Gemini environment has to date gone quite smoothly. Part of the reason for this success was the relatively early involvement of Engineering and Science in the Development project. Another was the dedicated effort each functional team invested to make sure their part of the project was successful. A clearly functional effort, is this the model for Gemini? Functional accountabilities with early involvement? A pseudo-matrix management approach?

Perhaps. Or perhaps we could evolve a bit more and continue to blend responsibilities and roles in a more matrixed approach. I think the Flamingos-2 functional approach can work, but I feel there’s more potential for true high efficiency with the matrixed model. Teams working together with joint accountability seems the higher efficiency model, although it is certainly not the only possible successful one. On the other hand, if you happen to own a Pontiac, you may be wishing for a return to Sloan’s GM.

While working for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, Scot started researching Alfred P. Sloan, his years at GM, and the origins of the Sloan Foundation. He was always amused when Hirsch Cohen, from the Sloan Foundation would introduce himself as being from the “other Sloan”. He is still amused whenever he has the opportunity to use facility plumbing manufactured by the (unrelated) Sloan Valve Company. He also views John Peoples, pictured above, as an incredibly effective manager who brought the SDSS through some very tough times by careful use of the right management tool at the right time.