When you hear the thundering herd behind you, it’s time to move on to a new field. That’s advice I often heard from my graduate advisers. While you might call this a “small science” mindset, they went on to found the Whole Earth Telescope (WET), an international collaboration of astronomers at more than a dozen observatories around the world that coordinated observations to follow variable (white dwarf) stars continuously for up to two weeks at a time, clearly a “big science” approach. The WET was initially very successful, and began to falter only later as it struggled to transition from a bunch of astronomers doing what they needed to do to get their science addressed, to an institution looking to continually justify its funding and purpose.

I recently finished Giant Telescopes by Patrick McCray, a book basically about the origins of the Gemini Observatory. I was struck at how many of the same arguments that were in the community decades before Gemini, persisted up to and through its construction and are still being debated today. Principally, the question of private vs. public and big science vs. little science. In my earlier posting about The role and need for an international observatory, I gave some of my thoughts on the first question so here, I want to at least introduce the latter.

A few years back, Simon White and Rocky Kolb submitted a set of papers, each championing for the big science or little science models for astronomy. There was even a pseudo-debate between them at the 2008 AAS meeting (http://aas.org/taxonomy/term/27 – session 87 – where you can see a video of the discussion). Simon White’s paper was Fundamentalist physics: why Dark Energy is bad for Astronomy while Rocky Kolb’s, issued in response, was entitled A Thousand Invisible Cords Binding Astronomy and High-Energy Physics. The context for this particular discussion was Dark Energy, but the underlying issue was really whether or not astronomy should be done in a big science or little science approach.

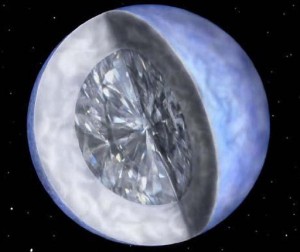

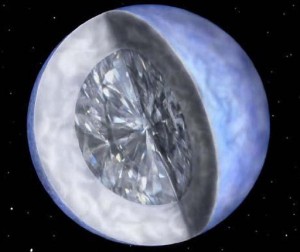

An artistic interpretation of the crystallized white dwarf star, BPM 37093, observed by the WET.BPM 37093 is so massive, that theory predicts its core, mostly carbon and oxygen, is crystallized. Here on Earth, crystallized carbon is called diamond. Observations of the oscillations of this star with the Whole Earth Telescope were consistent with this interpretation and placed strong limits on the amount of crystallization within the star, a diamond in the sky.

I don’t think this argument will ever really die since we will always have competing projects that are each done best under a different model. The solution is going to be to continue to adapt and be aware of the compromises and needs necessary to keep both approaches viable. One interesting moment in the 2008 AAS “debate” was when an audience member asked what each would like to adopt from the other side. Simon White said of high energy physics “managing large projects” while Rocky Kolb said of astronomy “making data public”. What I liked about this question and its responses was that it acknowledged that we don’t have to simply emulate the high energy physics big science model, nor steadfastly stick to astronomy’s traditional small science mode, but we can learn from both and make something better than either alone. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), like the WET, is a good example of this kind of approach. A core group of people inspired and really implemented the survey, with formal management and technical support partially adopted from the particle physics world. The SDSS used both public and private funding and made all the data publicly available after a short proprietary period. This melding of approaches helped make the SDSS one of the most successful projects of its type and certainly helped pave the way for even larger projects like the LSST and PanSTARRS.

So the question isn’t big science vs. small science in astronomy, but how do we create an environment where both can exist, cooperate, and thrive? With 30m telescopes, 8m surveys, and pushes to build large, wide-field survey imagers and spectrographs, astronomy must learn to embrace big science, although we can do so on our own terms, not necessarily on those laid before us by other fields and previous projects. This debate is similar to the one on public vs. private facilities. A true strength of the astronomy community is that both public and private facilities have been successful. That both are continuing to debate why they each need more resources than the other means the community is relatively healthy. The next hurdle in both these arenas will be how to ensure the appropriate levels of cooperation between each community. How do you motivate private funding when the data become public to all? How do you (or do you?) justify public funding when the resulting data remain private? How do you make sure individual contributions are visible and not an anonymous contribution to a juggernaut project? How do you handle risk in a extremely delicate, risk-adverse, funding environment, especially in a field which traditionally pushes at the outer limits of available technology, a fundamentally risky task?

I’ll try to address some possible answers to these questions in future posts.

Starting off with the Whole Earth Telescope, then onto the SDSS, Subaru, and now Gemini, Scot has been involved in increasingly “larger” science, but has always managed to come away with his own “small” science projects within each. He particularly enjoyed doubling the number of known white dwarf stars from SDSS data of largely failed attempts to find Quasars!